Friday, December 7, 2012

Jean Lurcat - Tapestries

1. The Sparrow-owl, 1954. 1m 44cm x 1m 10cm.

2. Blue Forest, 1953. 2m 05cm x 1m 50cm.

3. Blue Scarlet, 1953. 1m 70cm x 95cm.

4. The He-goat and the Astrapatte, 1949. 1m 50cm x 2m 45cm.

5. The Poet's Garden, 1955. 3m 60cm x 7m 15cm.

6. Wine and Music or the Little Grey Wine, 1954. 2m 22cm x 3m.

Thursday, November 22, 2012

La Fiesta de la Muerte

1. Calavera de Azúcar. A "sugar skull" executed in cardboard. By the Linares family. Mexico City.

2. An All Souls' Day offering in the Anahuacalli. By the Linares family. Mexico City.

3. Alegre carroza funeraria. An amusing funeral carriage in polychromed clay. Metepec.

4. Altar de Muertos. An All Souls' Day altar in a private home decorated with handcrafts from different regions of Mexico.

5, 6. A Zapatista skull "Judas". By the Linares family. Mexico City.

7. A Judas. Mexico City.

8. Miguel Linares giving the finishing touches to a cardboard "sugar skull". Mexico City.

9. the Linares family, excellent artisans in the making of "Judases", mask, "sugar skulls" and fantastic "alebrijes". Mexico City.

10. Judas alebrijado. A 10 meter high "judas". By the Linares family. Mexico City.

Death is a prominent theme in Mexican popular art, so familiar to us from the great sculptures of pre-Hispanic Mexico, of which the most outstanding example is the majestic and terrifying Coatlicue, Goddess of the Earth and of Life, who wears the mask of death, or perhaps the beautiful skull shaped in rock crystal by the master hand of an Aztec craftsman. The theme is perpetuated in the bittersweet humor of great popular cartoonists, such as Santiago Hernandez, Manuel Manilla and Guadalupe Posada, who highlighted events in the daily life of the people through the portrayal of figures of skeletons showing an ironic grin full of sarcastic humor in which Death is a personality with human traits, a friend or companion with whom we can make a joke. Diego Rivera said of Posada, 'His talent was as corrosive as the acid he used to prepare his etchings in holding up to scorn the Establishment of his day". "Posada: Death has become a carouser who fights, gets drunk, cries and dances". "A friendly death, a death which becomes a thing of articulated cardboard to be moved by pulling a string". "Death as a sugar candy skull, a death to feed the sweet tooth of children while their elders fight and fall dead or are hung by the neck". "A reveling death which takes part in dances and visits the cemetery to eat 'mole' and drink pulque among the graves." ". . . All are portrayed as skeletons, from cats and bean sellers to Porfirio Diaz and Zapata and including ranchers, artisans and 'dudes' as well as workers, farmers and even Spaniards". Although to a person from the Old World or one who has absorbed its culture the thought of death is a horrifying one, most Mexicans do not consider it as a denial of life, but rather as a complement to it and they accept it so naturally that they eat candy skulls, play with skeleton puppets to produce a macabre dance, buy the little figures known as "padrecitos" which have a chick pea for a head and which, glued to a strip of paper, march in a procession carrying a tiny coffin or gather around a tomb from which when a string is pulled a skeleton appears with a bottle in his hand. Death is also represented in all manner of clay or cardboard skeletons: cyclists, priests, "charros", mothers with children in their arms, street musicians who paradoxically assume oddly lifelike postures, even a couple dressed as bride and groom, ironically portraying Death as participating in the sacrament that perpetuates life! This is a basic idea which goes back to the very roots of the Indian half of Mexican culture. To the pre-Hispanic Mexican death is only a necessary prelude to resurrection; one must die to be born again and it is death which is the great creator of life. The celebration of the "Day of the Dead" (November 2) is a source of inspiration for the artisan who devotes part of his production to it: incense burners for the special altars honoring the dead in the homes or grave ornaments. Those from the State of Oaxaca are very beautiful as are those of Santa Fe de la Laguna in Michoacán, from the Barrio de la Luz in Puebla in black glaze known as "toritos" and surrounded by candles and marigolds, those of black glaze also from Metepec in the State of México, the polychromed ones of Matamoros, Puebla and Ocotlán, Oaxaca, about which are portrayed the dead souls as tiny figures clasping hands. In the states of Oaxaca, Jalisco and Guanajuato polychromed pottery toys representing death are made and in Toluca little tombs, animals, flower baskets and shoes of spun sugar are made for the souls of dead children. Altars are also decorated with garlands of tinfoil and tissue paper flowers and paper cutouts with allegorical figures as well as the traditional sugar candy skulls with tin foil and the names of dead relatives written on the bony foreheads. In Mexico City for All Saints' Day decorated sugar skulls are made and cardboard toys called "entierros" (burial processions) with a file of marching monks and a coffin pasted on a strip of cardboard.

2. An All Souls' Day offering in the Anahuacalli. By the Linares family. Mexico City.

3. Alegre carroza funeraria. An amusing funeral carriage in polychromed clay. Metepec.

4. Altar de Muertos. An All Souls' Day altar in a private home decorated with handcrafts from different regions of Mexico.

5, 6. A Zapatista skull "Judas". By the Linares family. Mexico City.

7. A Judas. Mexico City.

8. Miguel Linares giving the finishing touches to a cardboard "sugar skull". Mexico City.

9. the Linares family, excellent artisans in the making of "Judases", mask, "sugar skulls" and fantastic "alebrijes". Mexico City.

10. Judas alebrijado. A 10 meter high "judas". By the Linares family. Mexico City.

Death is a prominent theme in Mexican popular art, so familiar to us from the great sculptures of pre-Hispanic Mexico, of which the most outstanding example is the majestic and terrifying Coatlicue, Goddess of the Earth and of Life, who wears the mask of death, or perhaps the beautiful skull shaped in rock crystal by the master hand of an Aztec craftsman. The theme is perpetuated in the bittersweet humor of great popular cartoonists, such as Santiago Hernandez, Manuel Manilla and Guadalupe Posada, who highlighted events in the daily life of the people through the portrayal of figures of skeletons showing an ironic grin full of sarcastic humor in which Death is a personality with human traits, a friend or companion with whom we can make a joke. Diego Rivera said of Posada, 'His talent was as corrosive as the acid he used to prepare his etchings in holding up to scorn the Establishment of his day". "Posada: Death has become a carouser who fights, gets drunk, cries and dances". "A friendly death, a death which becomes a thing of articulated cardboard to be moved by pulling a string". "Death as a sugar candy skull, a death to feed the sweet tooth of children while their elders fight and fall dead or are hung by the neck". "A reveling death which takes part in dances and visits the cemetery to eat 'mole' and drink pulque among the graves." ". . . All are portrayed as skeletons, from cats and bean sellers to Porfirio Diaz and Zapata and including ranchers, artisans and 'dudes' as well as workers, farmers and even Spaniards". Although to a person from the Old World or one who has absorbed its culture the thought of death is a horrifying one, most Mexicans do not consider it as a denial of life, but rather as a complement to it and they accept it so naturally that they eat candy skulls, play with skeleton puppets to produce a macabre dance, buy the little figures known as "padrecitos" which have a chick pea for a head and which, glued to a strip of paper, march in a procession carrying a tiny coffin or gather around a tomb from which when a string is pulled a skeleton appears with a bottle in his hand. Death is also represented in all manner of clay or cardboard skeletons: cyclists, priests, "charros", mothers with children in their arms, street musicians who paradoxically assume oddly lifelike postures, even a couple dressed as bride and groom, ironically portraying Death as participating in the sacrament that perpetuates life! This is a basic idea which goes back to the very roots of the Indian half of Mexican culture. To the pre-Hispanic Mexican death is only a necessary prelude to resurrection; one must die to be born again and it is death which is the great creator of life. The celebration of the "Day of the Dead" (November 2) is a source of inspiration for the artisan who devotes part of his production to it: incense burners for the special altars honoring the dead in the homes or grave ornaments. Those from the State of Oaxaca are very beautiful as are those of Santa Fe de la Laguna in Michoacán, from the Barrio de la Luz in Puebla in black glaze known as "toritos" and surrounded by candles and marigolds, those of black glaze also from Metepec in the State of México, the polychromed ones of Matamoros, Puebla and Ocotlán, Oaxaca, about which are portrayed the dead souls as tiny figures clasping hands. In the states of Oaxaca, Jalisco and Guanajuato polychromed pottery toys representing death are made and in Toluca little tombs, animals, flower baskets and shoes of spun sugar are made for the souls of dead children. Altars are also decorated with garlands of tinfoil and tissue paper flowers and paper cutouts with allegorical figures as well as the traditional sugar candy skulls with tin foil and the names of dead relatives written on the bony foreheads. In Mexico City for All Saints' Day decorated sugar skulls are made and cardboard toys called "entierros" (burial processions) with a file of marching monks and a coffin pasted on a strip of cardboard.

Friday, October 26, 2012

Joseph Müller-Brockmann - Musica Viva - Zurich Tonhalle Posters

1. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1957

2. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1957

3. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1958

4. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1958

5. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1958

6. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1959

7. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1959

8. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1961

9. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1969

10. Zurich Tonhalle. musica viva. Concert poster, 1971

11. Zurich Tonhalle. Concert poster, 1958

12. Zurich Tonhalle. June Festival. Concert poster, 1951

13. Zurich Tonhalle. June Festival. Concert poster, 1951

14. Zurich Tonhalle. June Festival. Concert poster, 1959

His posters for the Tonhalle reveal an artist at work, as well as one who fathoms the world of communication, with a particular audience for a particular function. His posters are comfortable in the worlds of art and music. They do not try to imitate musical notation, but they evoke the very sounds of music by visual equivalents - not a simple task. - Excerpt from the Paul Rand's foreword for the book: "Joseph Müller-Brockmann, Pioneer of Swiss Graphic Design" -

Friday, September 28, 2012

The Wheel and the Smiling Apsara - photos taken in India by Gilbert Etienne.

1. Wheel of the chariot of the sun, 3 metres high. Konarak.

2. Detail of a wheel of the chariot of the sun, Konarak.

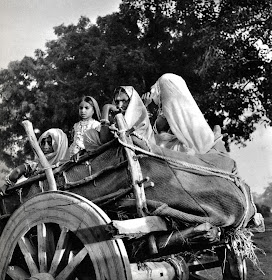

3. On the road from Gwalior to Agra, peasants on the way to the festival of Diwali at Morena.

4. Flying figure, Kailasa of Ellora, VIIIth century.

5. Detail of the Rameshwaram cave (No. 21) at Ellora, VIth century (?). The figure on the left represents the river goddess Ganga, on the right a protecting divinity.

6. Reliefs of cave No. 19 at Ajanta. The king and the queen of the snakes (naga) lords of the water.

7. Rameshwaram cave at Ellora, Shiva as Nataraja, king of the dance.

8. Cave temple of Elephanta, end of the VIth century (?). Shiva in his two aspects: masculine and feminine, leaning on his traditional steed, the bull Nandi.

9. Halebid, Mysore, the great Shiva temple. XIIIth century, Hoysala style.

10. Detail of the outer doorway of the temple of Mukteshwara, Bhubaneshwar, Orissa, about 975 A.D.

11. Sun Temple, smile of the apsara.

12. Meeting near Debal, Gharwal, Bara Khimanand and his daughter go down to the plain.

13. In the temple of Jembukeshwara, near Shrirangam, group of Brahmins, in the background the entrance to the cella containing the statue of the god and into which non-Hindus may not enter.

14. Statue of the Jain God Mahavir, X-XIth century, Nilkanth, Alwar district.

2. Detail of a wheel of the chariot of the sun, Konarak.

3. On the road from Gwalior to Agra, peasants on the way to the festival of Diwali at Morena.

4. Flying figure, Kailasa of Ellora, VIIIth century.

5. Detail of the Rameshwaram cave (No. 21) at Ellora, VIth century (?). The figure on the left represents the river goddess Ganga, on the right a protecting divinity.

6. Reliefs of cave No. 19 at Ajanta. The king and the queen of the snakes (naga) lords of the water.

7. Rameshwaram cave at Ellora, Shiva as Nataraja, king of the dance.

8. Cave temple of Elephanta, end of the VIth century (?). Shiva in his two aspects: masculine and feminine, leaning on his traditional steed, the bull Nandi.

9. Halebid, Mysore, the great Shiva temple. XIIIth century, Hoysala style.

10. Detail of the outer doorway of the temple of Mukteshwara, Bhubaneshwar, Orissa, about 975 A.D.

11. Sun Temple, smile of the apsara.

12. Meeting near Debal, Gharwal, Bara Khimanand and his daughter go down to the plain.

13. In the temple of Jembukeshwara, near Shrirangam, group of Brahmins, in the background the entrance to the cella containing the statue of the god and into which non-Hindus may not enter.

14. Statue of the Jain God Mahavir, X-XIth century, Nilkanth, Alwar district.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Hand Painted Films

1 - 7. Norman McLaren - hand-painted 35mm film fragments.

8,9. Stan Brakhage - Out-Takes - University of Colorado Boulder (1991) - hand-painted 70mm-IMAX film strips.

10, 11, 12. José Antonio Sistiaga - Ere erera baleibu izik subua aruaren (1968-1970) - hand-painted 35mm film fragments.

8,9. Stan Brakhage - Out-Takes - University of Colorado Boulder (1991) - hand-painted 70mm-IMAX film strips.

10, 11, 12. José Antonio Sistiaga - Ere erera baleibu izik subua aruaren (1968-1970) - hand-painted 35mm film fragments.